Conjectures

Fathers and Sons, Sons and Lovers

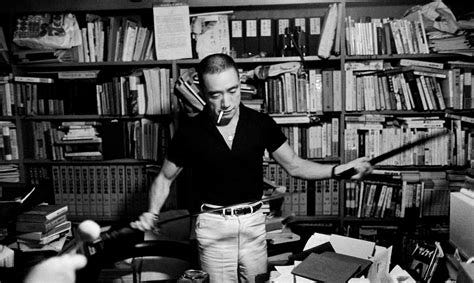

I’m reading Mishima’s Sun and Steel ahead of tonight’s salon—it’s a brilliant work, thoughts on the relation of language and mind and body that I was unprepared for. (In a comment online, I ludicrously compared it to Cusk’s Outline trilogy—but, weirdly, I do think there’s some similar impulse: losing faith in the objective form of the novel; the novel disappears into the absent-center of a monologic account: absent in this case because, redirecting his consciousness from the depth to the muscles, the surface—the outline!—he becomes a kind of embodied void of thought. This seems insane, but oddly makes sense.

Response to a comment by a friend (gay) on the (straight) male imagination: “The normative male imagination seems obliterative: objects of aggression are to be destroyed and eliminated (not sadistically tortured, which brings them too much into presence), and objects of Eros are to be idealized out of their particularity. If it is by objects that the subject is constituted, then this implies a corresponding self-forgetting, self-unknowing, in the straight male psyche, which I think is also the case. Which is why an intense focus on women, intense interest in women—what one might think to be the most heterosexual thing—is in fact slightly ‘suss’ from a straight perspective. I think, e.g., Swift’s poem on Celia does suggest a certain degree of abstraction/idealization as central to the heterosexual male imagination, whereas intense focus on sensuous particulars seems, among us, to be associated with a spectrum of fetishisms, from sadism to necrophilia. (I have written down in my notebooks somewhere: ‘A sadist always seems effeminate—too aware of others’ pain.’)”

Then again, consider those heroes of intensest love, intensest, most delirious desire, senses keyed up and pulsing to enumerate the last quality, the least, last lash of the beloved’s body. Think of such love’s link to death—of, in a doomed heroic instance, James Ellroy’s quest after the lost object of desire, the dead Mother, in My Dark Places: his enumeration of the places and times and marks and means of her murder.

Lear is a tragedy of demystification in which the Patriarch is revealed as Nobodaddy—Noah like a drunken Silenus, here beheld by daughters, not sons. The father is revealed as the son—as somebody’s son (“we come crying hither”)—though too late, and his death redeems no one. (The young seem diminished rather than aggrandized by this spectacle: even Edgar speaks of Lear’s sufferings as exceeding all others’, exemplary in their excess, as of the giants from before the Flood: “we that are young / Shall never see so much nor live so long.” (Knock on wood. Spit, spit.)

Parturition brings forth mortality. The mother bears Lear:

What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap

Honey of generation had betrayed,

And that must sleep, shriek, struggle to escape

As recollection or the drug decide,

Would think her Son, did she but see that shape

With sixty or more winters on its head,

A compensation for the pang of his birth,

Or the uncertainty of his setting forth?

These lines—there is something ungeheuer in them. The woman who loves an aged man has forgiven him for growing old—has decided his life was worth it, all life was worth it.

Remembering when, as a child, my father told me what “hookers” are—“They’re someone who pretends to love you”—and thinking how true that was.

To be photographed is not to be at leisure. Leisure is unrecorded and can be known only by its effects.

The man in the photograph, at best, resembles a man at leisure. Whether the photographic subject is conscious of being photographed or not, is immaterial—just as it makes no difference if the seeming is to others or to oneself. If the former: a performance, not leisure. If the latter—well. Suppose I told you that, during your apparent leisure, unbeknownst to you, a small, whirring, imperceptible machine had crept up on the slackened tendons of your moments and, without your knowledge... severed them! Sliced out a small segment! What then?

The Son got the obscure impression his Father was crowing when he told him, having come to his house to help out with his own son while his wife was out of town, that Val Kimer had died—which he knew his Father would have known about, having come on the train, with his phone, which he would have had to swipe to receive its IV drip of news. He got the obscure impression his Father was crowing. “He was a Christian Scientist,” his Father said—i.e., one whose religious beliefs did not permit him to undergo medical treatment. “He died of pneumonia, he was a Christian Scientist.” The Son demurred at this, declined to pursue the matter further. “He had had cancer,” he said. “He had undergone treatment,” he said, repeating the little he knew, trying to deflect the crowing. “Yes, with religious beliefs everyone draws the line differently,” his Father intoned, sententiously—meaning, the Son supposed, that with anything so irrational as religion, we all have our sticking-points, we all have that moment that marks the wearing-down of our resistances, exposing the raw bone. But I would not like to have held against me the sum of my minor transgressions, the Son thought—as if the minor transgressions were the sum total, as if they, products of moments of weakness, of whatever kind (fear, familial love, obligation) negated the core of my being—gotcha! So, suppose he had received proper treatment for his pneumonia (and I gather, now, having read a bit more into it, that he did receive treatment for cancer, but was shocked by it, left without any wish for further interventions)—suppose he had done so, he would have had, what a few more years? Years as what? Not as himself. Surely that must be our premise: that we are not obligated simply to acquiesce in whatever is best for us, abstractly, ourselves considered as a better or less-well functioning machine. Let him die, I say. Let him live, the Son thought.

Boy’s first haircut today. Suspense like that of the magic hour: how long could this perfect calm be sustained. Lasting, lasting, lasting—like water purling endlessly over a weir.

Duckrabbit: he looks like my father then I look down over the bridge of his nose; like my wife’s brother when I look at him in the mirror, head on.

Boyo riding my shoulders as I hand him up an icecream destined to hover precariously above my head. Me, fishing in my wallet: “I’m taking a risk here...” Ice-cream truck guy: “Life is a gamble, right?”

Enjoyed all of this, and especially the second. Books could and probably have been written disputing it...

I had the idea of writing a play about Mishima visiting NYC. Now it seems I'll have to read Sun and Steel.